by Ron Raskin

When the ruling elites of a country decide to pursue a particular objective, they develop a strategy that is usually too complex to share with the general population. To align the nation with this strategy, they accompany it with a narrative—something easy to sell to the public, a simple message for the common people.

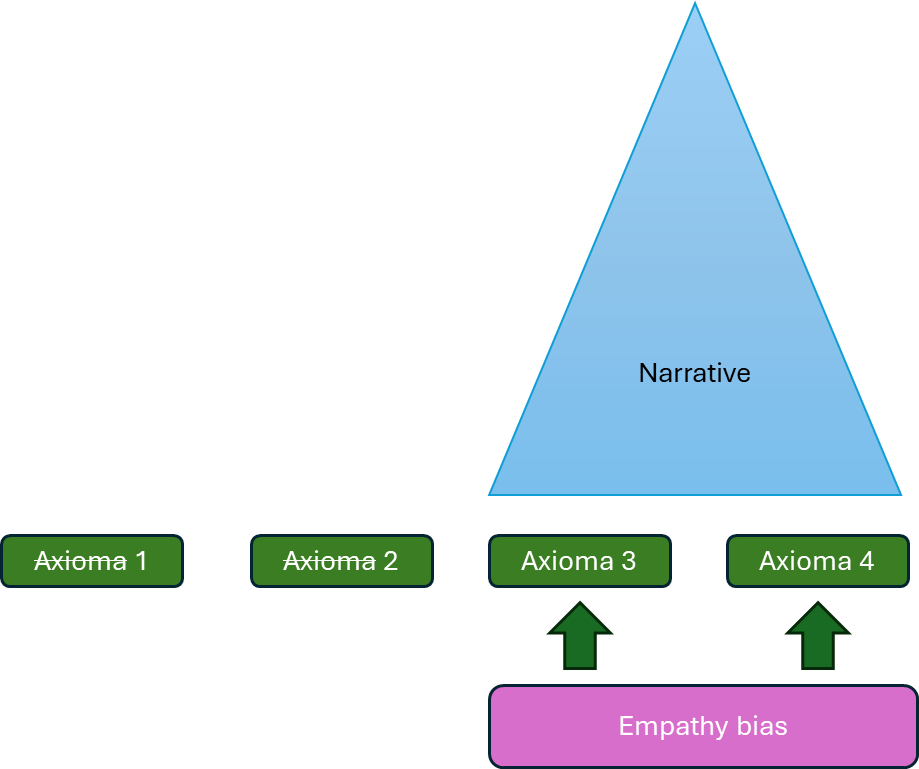

Like any theory, a narrative is based on basic ideas (axioms). For example, the idea that two parallel lines never meet leads to Euclidean geometry, while believing they do meet leads to a different kind of geometry called hyperbolic geometry. Changing the basic ideas leads to a different story or worldview.

These basic ideas (axioms) are usually based on belief, which often comes from our natural human tendency to feel more empathy for people who seem like us. This is then strengthened by the way information is shared to support certain emotions. The strongest emotions—love and hate—are often used as the foundation to support these beliefs.

Now that we have a theoretical understanding of narrative anatomy, we are ready to dive into a specific case: the Russian case:

In the Russian case, the feelings are:

- We have been a great nation, and that remains a source of our pride.

- We fought and saved the world in World War II—in Crimea, Kharkov, Odessa, etc. Millions of Soviet/Russian soldiers died there. We paid a huge price defending these places, so how can anyone say they are not our land? It’s just a fraud to take them from us.

- The Soviet Union wasn’t perfect, but there was stability, low crime, and hope for a better future. Now we have nothing – not even our pride. The West and democracy has taken it away from us.

These feelings then cement the following axioms of the Russian narrative:

- Liberalism equals selfishness.

- The liberal West is driven solely by self-interest and selfishness.

Based on these axioms, the following narrative is easily constructed:

- Globalization is a tool used to dominate and exploit other nations for the benefit of the West.

- Anyone who has power will eventually use it; therefore, NATO’s eastward expansion is extremely dangerous—it’s only a matter of time before it is used to take whatever the West desires.

- The Soviet Union/Russia was betrayed and deliberately manipulated in order to be destroyed—this should be seen as an act of aggression. Therefore, Russia has the right to fight back and restore its territory and influence by any means necessary, in accordance with the principles of realpolitik and the balance of power, to make the world a better place.

- Russia and liberalism are incompatible, and pushing liberal values onto Russia is simply a way to destroy it.

Now, to fully understand the narrative it is of course very helpful to understand the philosophy and the strategy behind it. To do so in the Russian case we need first to talk about Alexander Dugin, his definition of Dasein and his Fourth Political Theory. Not because Putin and his elite is based on Dugin’s theory but because Putin and his elite in many ways come to somewhat similar conclusions. Talking Dugin’s language: Dasein of both Dugin and Putin is pretty much the same thus leading to the similar conclusions.

From Dugin’s point of view, Dasein is spiritual soul of humans that comes from a people’s connection to their land, history, religion. Would you be ready to live according to Sharia lows? Would you be ready to live in North Korea or rather prefer to fight and to die if necessary for your way of life? So far so good.

Based on this idea, Dugin claims that people with the same Dasein have the right to live in their way which is essentially the essence of his Fourth Theory focusing on Dasein, where the first three are:

- Liberalism (focused on individual freedom, like in the West today)

- Communism (focused on equality and class struggle)

- Fascism (focused on nation and race)

From Dugin’s point of view liberalism itself is not a true Dasein. It is a political theory—specifically, the dominant ideology of modernity—and one that works to suppress or erase Dasein altogether.

It is not very clear to me why liberalism with its basic values can not live along someone Dasein. For me Dugin’s Dasein sounds like partially orthogonal to the three theories. There is of course relation between Dasein and prevailing political ideology, but they are not mutually non exclusive. And indeed, when talking for instance, about Israel Dugin finds itself in paradox where Israel is seen on one hand as a nation with deep roots, identity and Dasein making it natural ally of Eurasia and as country that aligns with Liberal West on the other hand making it an enemy of Eurasia. Similarly, when talking about Japan that succeeded as Liberal Democracy, Dugin claims that it is not really liberal deep inside but only wearing a mask of liberalism rather than to assume that liberality is simply a layer above Dasein or layer inside multilayered Dasein.

Anyhow, for Dugin because Russian Dasein is fundamentally:

- Communal over individual (well expressed in Russian phrase: “Give your last shirt to a friend”. Nice dream that has no much to do with Russian reality but does influence Russian romantical thought and world perception)

- Spiritual/metaphysical over materialist

- Tragic and mystical over optimistic and rational

- Orthodox over secular

And because liberalism—defined as:

- Radical individualism

- Secularism

- Progress-worship

- Globalist homogenization

Thus, liberalism is the opposite of Russian Being. It’s like trying to plant a cactus in a swamp—it simply doesn’t grow without destroying the swamp. In Dugin’s view, if Russia fully accepted liberalism, it would cease to be Russia.

When talking about Gorbachev’s and Yeltsin’s reforms—which sadly failed—Dugin’s theory would interpret their failure as inevitable, arguing that they were doomed from the start because they didn’t align with the Russian spirit, or Dasein. But in reality, these reforms failed mostly because they were poorly planned, driven by an overly romantic view of capitalism and democracy in the late 1980s, and because of unfavorable conditions for the Russian economy to succeed in its economic reforms during the 1990s.. The failure wasn’t about Russia’s deeper nature—it was mostly just bad luck and poor decisions. In fact, Russians living in the U.S., Western Europe, and other liberal democracies often integrate very well into those societies.

According to Dugin, based on the idea of a unique Russian Dasein, Russia is not a European country but the center of a separate Eurasian civilization. He believes Russia should align itself with other non-liberal countries like Turkey, India.

In Dugin’s thought, coexistence with the liberal West is impossible unless the West abandons its globalizing ideology. For Dugin, Eurasia and the liberal West are not just geopolitical opponents—they are opposite worlds. One seeks sacred difference, the other demands universal sameness. Eurasia is not just a region—it is the last defense of metaphysical plurality against a liberal monoculture. Which means that their coexistence is not possible—only resistance, separation, or eventual conflict.

Overall, Dugin’s Fourth Political Theory is more of a geopolitical strategy than a true philosophy and can be seen as yet another attempt to create a “Valores Nation”: a political structure that transcends traditional nations and is grounded in shared values, or “valores”. It uses complex language and ideas (essentially a narrative) to justify Russian imperialism and is rooted in an attempt to find someone or something to blame for Russia’s failure. Personally, I’d suggest that Russian intellectuals stop leaping from one grand, world-saving theory to the next, and instead remember the core principle of conservatism: society is too complex to fix with abstract ideas—we need to build on inherited wisdom and real-life experience.

Anyhow, that’s what Dugin and Putin actually believe: Russia can’t adopt liberal democracy because it just doesn’t work for Russians. From that belief, everything else follows. They think Russia must take its own unique path, and to succeed, it needs enough resources—especially people. In today’s world, a country can’t truly be independent without influence and strong political and economic ties with around a billion people. That’s why Dugin promotes the idea of a Eurasian empire, and why Putin is waging war against Ukraine and attacking liberal values. The liberal world is seen as the enemy because it’s viewed as trying to force values onto Russia that it can’t live by. From their perspective, if Russia follows those values, it won’t grow, and it will collapse.

Most Russians don’t really care about big theories. To them, liberals and oligarchs are basically the same. They see Putin as just another tsar with all its pros and cons. They feel that places like Crimea were taken from them and rightfully belong to Russia. They’re also concerned about the rise of Islamic extremism, and for the most part, they just want a normal life—like people have in the U.S. or Western Europe. Hopefully, one day Russians will find their path to success and stop torturing themselves and everyone around them.

Final note: Anyone who chooses to engage or negotiate with Russia should understand that its elite isn’t simply trying to get a good deal. At least partially (it is not clear how much Putin himself truly believes in Dugin’s theory or just uses it to further Russia’s interests), it is driven by an idea—one that makes today’s Russia fundamentally incompatible with the West. This won’t change until that idea collapses and new ones emerge to replace it.