By Ron Raskin

Today’s economy favors high productivity and high income per person. The environment is very competitive, and the time and energy required for success make it hard to support large families. Social norms also don’t encourage having more children. This leads to a decline in the influence of Western democracies in the global economy and geopolitics:

- Europe’s share of the world population has decreased from almost 28% in 1913 to just over 9% by 2024.

- The U.S. population increased from a little over 5% in 1913 to above 6% at its peak in the mid-20th century but has since dropped to less than 5% today.

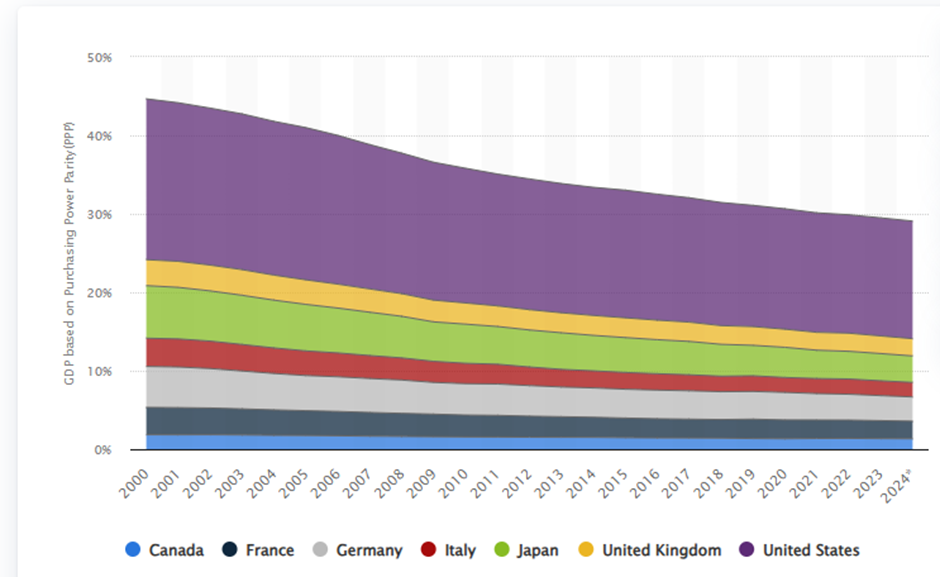

- The GDP of major Western democracies has also fallen from approximately 45% in 2000 to less than 30% today.

To avoid a demographic and, in turn, economic, military, and political collapse, fundamental changes in social norms and economic principles are needed.

The current economy is built on three main principles:

- The smarter and more capable you are, the more you earn.

- The more time and effort you invest, the more you earn.

- The higher the risks you take, the greater your potential earnings.

Nothing in this list prioritizes bigger families, and no economic stimulus policy for more children has ever challenged these basic cornerstones. So, how can we create a new social contract and economic model that prioritizes larger families while ensuring that individuals are still well-educated and socially integrated? This is a difficult balance to achieve.

Of course, Western governments around the world are aware of the demographic challenge and have proposed different solutions to address it. For example, the EU has created a “toolbox for action,” and South Korea has presented its own plan. Unfortunately, these solutions seem too little, too late, mainly focusing on financial incentives. To truly solve the problem, we need to address deeper social and economic issues, as the roots of the problem go much deeper. People’s view of reality goes beyond just their purchasing power; they are social beings who need respect, self-realization, and more. This means that larger families should be supported both socially and economically.

There are also other economic ideas, like the Time Bank Solution, aimed at solving social problems, including the demographic challenge. However, so far, these ideas haven’t proven effective or have provided only limited solutions.

The goal should be to ensure that larger families have both social and economic advantages while still encouraging education and hard work. This change should improve the current situation, not replace it. In other words, besides offering financial incentives and parental leave, we need to make sure that people who spend more time and energy on their children also have higher social status, income, and opportunities. This brings us to the fourth key point:

- If you have more children, without sacrificing their education and development, you should have more opportunities and a better income.

For example, larger families could have more voting power based on the number of children under 18 and the effort invested in raising them. Both the public and private sectors could prioritize jobs for people with larger families. In education, children from bigger families could be given priority in universities. Road public lanes should be allowed for parents having bigger families to save them time. They also should be prioritized in any queue in all government services. Competitions and awards could celebrate families in various fields like music, sports, or culture, such as recognizing the best family band or the best movie with family actors.

Every part of the economy and society should support larger families. The economy should recognize that parents with more children have less time for their careers and should adjust their rewards to account for that effort. Society must ensure that time spent with children is valued just as much as time spent working. This could include measures like limiting weekly working hours. While it may seem like this could harm the economy at first, it could actually do more good in the long run. Parents would be able to spend more time with their children without losing out on competition. The overall GDP might dip temporarily, but it would be rewarded later with a larger population.

It may seem like this would reduce quality of life or make it harder to afford things like a house, but that’s a misunderstanding. Even with GDP growth, housing often becomes less affordable because the cost of services, including housing, is tied to income. As average income rises, service costs increase too. Limiting working hours would lower income but would also lower essential costs, like housing, in a similar proportion.

This policy might resemble current affirmative action policies or support for the elderly, but it goes much further by changing both our economy and society.

Clearly, such a shift could create the opposite problem: the risk of economic failure, so it must be carefully balanced. The change should be gradual, with each step assessed for its effects, and the overall goal should be to optimize future national GDP, rather than focusing on current GDP or, even worse, current GDP per capita.

Note that in the fourth cornerstone, “time and energy spent” is used instead of “number of children.” This is to ensure that children grow up to be valuable members of society, not a burden.

To do this, we need to develop measures that can predict the future, based on the time and energy parents invest in their children. Fortunately, we already have some indicators, such as educational achievements. Ultimately, the more time and energy parents invest in their children, the more skills their children will have. And the better the children’s skills and education level, the better the overall outcome for society.

As a result, the government should monitor children’s development, taking into account their parents’ background (to ensure fairness between wealthy, educated families and poor, uneducated families). It’s not about comparing skills themselves, but rather comparing the change in skill levels. Clearly, creating a system that tracks these complex and debatable measurements won’t be easy, so initially, it will be simpler to base policies on parameters like the number of children, and more sophisticated tools can be introduced later.

Of course, not everyone can have children, so policies should be adjusted to support those individuals as much as possible, helping them adopt or have children. The laws should also be adjusted to support single mothers and fathers who need to raise children alone.

Perhaps one day, we also fill find the way to change the first cornerstone: “If you are smarter and better fit for the needs – you earn more”. Replacing it with: “If you achieved skills that are better than it would be expected from you – you earn more” but that’s another story.