By Ron Raskin

Since the beginning of humanity, groups have frequently competed over resources, leading to confrontations as part of the struggle for survival. These conflicts often have an interesting side effect: they push groups under pressure to unite, either by choice or by necessity. Over time, these temporary alliances of diverse groups can transform into larger, more homogeneous societies. From a thermodynamic perspective, this represents an increase in system entropy as shared traits and empathy circles spread throughout the population.

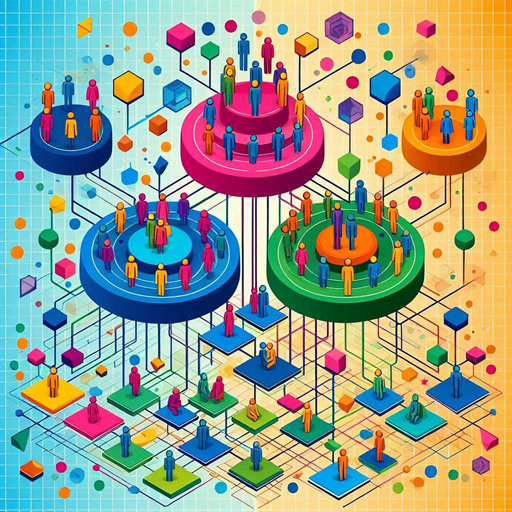

For those familiar with clustering algorithms, the structure of human societies resembles a process of bottom-up hierarchical clustering, where competitive pressures gradually merge smaller clusters into larger, unified ones.

Today, most people around the world live within countries defined by national identities. As English historian G. P. Gooch explains, “While patriotism is as old as human association and has gradually widened its sphere from the clan and the tribe to the city and the state, nationalism as an operative principle and an articulate creed only made its appearance among the more complicated intellectual processes of the modern world.”

National identity began to take shape with the French Revolution, transforming Europe throughout the 19th century and continuing to shape global dynamics. However, starting in the 20th century, new social structures emerged that extend far beyond national borders. These structures are not founded on shared ethnicity, language, or territory, but rather on broader social values.

Through the theoretical lens described above, we can now revisit and re-examine some major developments of the 20th and 21st centuries from this new perspective.

Proletarian internationalism

The early 20th century was marked by intense violence and upheaval, especially in Europe and worldwide. In 1917, following three years of war, the Bolsheviks took control of the former Russian Empire and formed the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Their goal was to propagate Communism globally, underpinned by the principles of proletarian internationalism. Though Stalinism later modified this vision considerably, the concept of a united, international working class endures.

A key aspect of this vision—one of the first with a global reach—was its belief that the working class shared more common interests than those defined by nationality, introducing a new framework for categorizing societies. However, the project faced significant challenges. A fundamental flaw was the assumption that proletarians within and beyond Russia had more in common with each other than with individuals from other classes in their own countries. The idea that all proletarians formed a homogeneous group proved overly simplistic. Not surprisingly, some workers chose to prioritize personal power over collective welfare, while others favored national interests over international solidarity. Ultimately, diverse motivations and human nature challenge such sweeping assumptions.

Wilsonianism

Perhaps in response to Bolshevik ideology—or perhaps independently—U.S. President Woodrow Wilson proposed his famous 14 Points, which became known as Wilsonianism. This could be seen as an alternative global mission, advocating for the spread of democracy and capitalism. While Marxists-Leninists believed communism was inevitable, Wilson believed the same of democracy. Rather than establishing an organization akin to the Comintern, Wilson promoted the League of Nations, proposing a global cluster of human society built upon a more granular, national framework.

Though the League of Nations, and later its successor, the United Nations, achieved some positive outcomes, they ultimately fell short of creating a unified global governance structure. The effort to establish a central governing body was unlikely to succeed, as it lacked a crucial element: external pressure strong enough to unite all nations, which was overshadowed by the internal differences that set them apart.

Arab League

Another effort to create a larger alliance transcending national borders was the Arab League, established in 1945. The concept seemed promising, as the Arab nations share many cultural and historical similarities, making such an alliance appear natural.

However, the League struggled to achieve true unity. Once again, divergent interests among the ruling elites and leaders of each country proved too great, overshadowing any external pressures that might have otherwise encouraged Arab nations to unify.

Islamic Fundamentalism

Islamic fundamentalism emerged as an idea between the late 19th and early 20th centuries. By the 1970s, it was initially seen by the West as a counterbalance to Communist ideology, but it quickly became a significant force in its own right. Islamic fundamentalism has two primary branches: Sunni and Shia, both of which have parallel movements.

Like other missionary ideologies, Islamic fundamentalism seeks to spread its influence, envisioning Islam as a universal foundation for humanity. This mission often clashes with alternatives such as Western liberalism and democracy. While it may not achieve global dominance, it can certainly cultivate a regionally expansive empire based on these principles, with Iran as a leading Shia power and Sunni nations like Turkey potentially aspiring to take the lead in Sunni fundamentalism.

The ultimate outcome of this movement, and the level of suffering it may cause, remains unknown. At present, there is no significant external pressure on these nations, which often plays a role in fostering cohesion. However, it seems that leaders of these movements are actively inviting such pressure to strengthen a unified Muslim identity.

European Union

The European Union represents the latest and arguably the most successful attempt to create a framework that transcends national borders. Its main strategy has focused on increasing internal cohesion within EU member states. For many years, the EU enjoyed relative stability and faced minimal external pressure, allowing it to concentrate on fostering unity. However, the landscape is shifting as the EU confronts significant demographic changes. The original European population is declining rapidly, while many immigrants are drawn to Islamic fundamentalist ideologies instead of embracing the liberal democratic values promoted by the EU.

As a result, two conflicting forces are pressuring the EU: an internal centrifugal force led by far-right groups advocating for a halt to immigration—potentially at the cost of EU unity—and external pressures from both established powers and rising nations like Russia, China, and Iran. This external influence could be beneficial to the EU project, provided that the pressures remain manageable.

Summary

Throughout the last century, various initiatives have sought to create broader structures that transcend traditional nations, grounded in shared values or “valores” (from Latin). The pressing question now is not whether we will see the rise of “Valores Nations,” but rather when it will happen.

Currently, two prominent attempts to create such nations are underway. The success of Islamic fundamentalism could usher in dark times for the world, while the success of the European Union might offer hope for liberal and democratic nations. Interestingly, the outcomes of both movements are interconnected; the pressures each exerts on the other could significantly influence their respective successes or failures.

Let me finish with a question: What about other small democracies outside the EU, such as Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, or Israel? Can they survive in today’s changing world? And can the EU itself survive on its own, without stronger alliances with other democracies, including the US?